In late September of 2001, just a couple of weeks after the 9/11 attacks, I was sent a mass email with the full text of an article from The Onion pasted into the body. The Onion had only recently entered the general public consciousness. I had just heard of it that year and had started receiving the occasional email promoting satirical news articles.

I saw right away that this article was about the terrorist attacks that had emotionally debilitated all of us only a few weeks before. I was 17, a senior in high school, and this was the first major national tragedy over which I remember feeling a true collective sadness. I couldn’t believe The Onion could possibly make a joke at a time like this.

The title of the article was “Not Knowing What Else To Do, Woman Bakes American-Flag Cake.”

The article was about a 33 year-old in Kansas who described her heartache, the same one I had at the time, as she watched the news depict something that was happening to some people in New York and a few other places—some people who weren’t her.

“Feeling helpless in the wake of the horrible Sept. 11 terrorist attacks that killed thousands,” it began, “Christine Pearson baked a cake and decorated it like an American flag Monday.”

The article said Christine planned to bring the cake to the house of her friend, Cassie Overstreet. It quoted this fictional Kansan at length as she detailed her process for baking the cake and the reasons she did it. “I thought I’d make something special or do something out of respect for all the people who died. All those innocent people. All those rescue workers who lost their lives.”

It’s so simple that it’s silly. Funny, but not in a way that will make you laugh. The idea that some idiot in Kansas thought baking an American flag cake was the appropriate response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. As though that would help in any way.

The article goes on. “‘I baked a cake,’ said Pearson, shrugging her shoulders and forcing a smile as she unveiled the dessert in the Overstreet household later that evening. ‘I made it into a flag.’

Pearson and the Overstreets stared at the cake in silence for nearly a minute, until Cassie hugged Pearson.

‘It’s beautiful,’ Cassie said. ‘The cake is beautiful.’”

That’s the end. The article doesn’t bother trying to say any more.

I remember staring into my parents’ boxy computer in 2001 and feeling like the wind had been knocked out of me. I couldn’t explain why but the article felt like the most cathartic reporting I had seen in those few weeks. But it was so stupid. And fictional.

The Onion’s ability to harness our collective hopeless energy and put it into an imaginary midwesterner who sliced strawberries to lay on a sheet cake to make the red stripes of the American flag made us feel seen, if not exposed in some way.

Over the next many years whenever there was any kind of national tragedy—any collective sadness—I found myself thinking about Christine Pearson and her stupid cake. How she made it because she didn’t know what else to do. How that seemed so insufficient, but also relatable. Because sometimes you just don’t know what else to do.

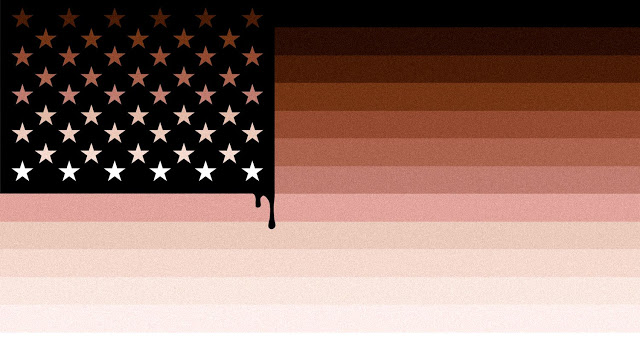

And then last week I saw our world start melting down because of yet another horrific killing of a black man by a white police officer. Because of yet another unforgivable injustice. Because these things don’t seem to be getting better.

I saw my most thoughtful friends sharing their insight and prayers. I saw them start to speak with cracked voices before shaking their heads. I saw them say they felt sad and hopeless. I saw them baking their proverbial cakes “not knowing what else to do.”

I ran by a Salt Lake City Unitarian church on Friday afternoon and witnessed a group of white people out front—not knowing what else to do—propping up a Black Lives Matter sign on the lawn.

I saw white people driving by—not knowing what else to do—honk and wave at the Unitarians.

I saw white people I follow on Twitter—not knowing what else to do—try to amplify the voices of their black friends by sharing their tweets about what this moment feels like for them.

I saw white people I follow on Instagram—not knowing what else to do—post images of black squares in an effort to make a record and add their emotional support to the ubiquitous heartbroken choruses.

I guess I even saw myself—not knowing what else to do—sit down at my computer late on a Friday night and start typing this article.

It all feels so similar to tragedies we’ve experienced before. So sad. So helpless. So empty. Unifying to the point that it prompts a uniform change of profile photos and a calculated unison use of hashtags.

I have to admit, every year I understand Christine Pearson from Kansas a little more. Every time I hear about a new tragedy I don’t know how to reel in, I think of her damn American flag cake and my throat immediately tightens up.

I understand the impulse to throw our hands up and say we don’t really know what else to do. The fatigue that makes us lose steam on issues where we aren’t personally victimized by whatever is causing so much pain. The temptation to hope and pray for the healing of a community that desperately yearns for healing, and then wish that hope was enough.

But on this issue, white people are far past the point where we can simply bake a symbolic cake or shed tears. We’re past the point of being allowed to simply surrender because we don’t know what else to do. Black people in our communities are not benefiting by our heartache for them. They're not protected by our desires for a better world. They don’t have the luxury of relying on our best wishes and intent, no matter how sincere.

For our Black Lives Matter signs and our tweets and our dark Instagram squares and these stupid internet articles to actually mean something, we have to actually do something. There are actions we can take right now. We can donate; we can march; we can speak; we can listen; we can learn; we can educate ourselves; we can protect; we can change. I’m sure there are other things too, and if you’re a white person (like me), it’s on you to figure out what those other things are.

If you’re white (like me), it might be tempting to feel like this tragedy (of our own making) is like 9/11 or anything else in our history that has made us collectively sad. We need to resist the impulse to group this one with all those other tragedies. This one is different, in part, because although baking the proverbial cake can sometimes be a comforting gesture, not doing anything more makes us complicit in failing to eradicate this evil. Although the proverbial cake can show that on some level we know we need to care, it’s meaningless if we’re otherwise silent–or worse, if we’re otherwise amplifying ignorant messages that crowd out the hard truths we need to hear.

So this time we have to do more than feel sad. More than flounder in helplessness. More than thoughts and prayers.

If you’re a white person, please consider this your problem to fix. If you’re not a white person, please know I’m going to do more than make cake.

I promise to continue to listen and search to discover what that “more” needs to be, no matter how much I struggle to figure out what else to do.

(Design: Joshua Fowlke) (Editor: Rachel Swan)