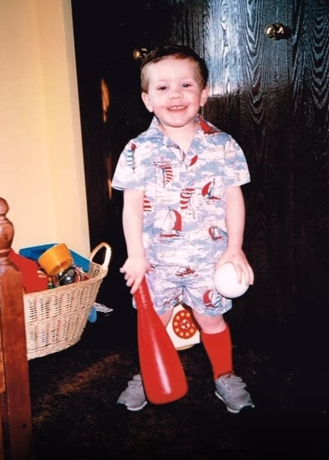

I was enrolled in T-ball at age five. My parents were going to make a sportsman out of me.

I didn’t understand the sport, and to be honest, I was only there for the donuts. At the end of our last game of the season we were each handed a participation trophy, the only way I was ever going to be rewarded for the sports. My parents still have in their possession a picture of me holding two donuts. My participation trophy is on the ground.

Eventually I upgraded to machine pitch, despite having never successfully hit the ball off of the tee. My only memory of my time in the fast-paced world of machine pitch is when I was sitting somewhere in the outfield when I saw something out of the corner of my eye move past me.

Everyone on the field began screaming my name as I stared at them, wondering why they wanted my attention. Eventually another boy ran toward me, picked up the ball that had landed a few feet from me, and threw it to someone else.

I didn’t stand up once during this entire event.

My friends and I joined a soccer team in the sixth grade. We called ourselves the Jolly Green Giants. And we lost every game.

None of us were really into the sports, although we tried desperately to get better at them.

At the end of my street there was a coldesac and we spent nearly every afternoon in that culdesac playing baseball. We played until our game was interrupted by Betty, a woman in her late 120s who sat on her front porch knitting all day, every single day.

Betty had a practice of throwing her yarn out into the yard and then screaming at us to come and help her get it.

We were all deathly afraid of Betty for reasons I’ll soon get to, and so we had a neighborhood pact that no child would ever have to go retrieve the yarn alone. We would all go together.

And we did. Every. Single. Day.

The moment we arrived at Betty’s porch, yarn in hand, Betty would demand that we sing for her.

The singing would last well over an hour, until Betty would initiate the grand finale and send us home.

Betty was in a wheelchair. She was an amputee. Her leg had been cut off about five inches from her pelvis. And at some point she had mistakenly come to believe that we, children of the neighborhood, desperately wanted to see her leg stump.

And so, she would remove her prosthetic leg, slowly, like this was a strip show at some trashy bar.

To this day, the sound of something being unclipped still gives me anxiety.

To this day, the site of hotdogs still terrifies me.

Our relationship with Betty continued for over a year, until one day Betty’s daughter-in-law, who also lived at that house, had a psychotic break and drove her car across every yard in the neighborhood before crashing into the back deck of one of the houses.

We, the children of the neighborhood, spent the next three afternoons after school inviting children of other neighborhoods to view the carnage on guided tours of our understanding of the path the car took.

Later that year, having not really improved at The Sports due to those series of distractions, I enrolled myself in Jr. Jazz.

For those unfamiliar, Jr. Jazz is not a music group. It is a basketball league for Utah’s teenagers, named after the Utah Jazz. For a small fee, a child could play basketball every Saturday for four months and then at the end of the season, the least-known basketball player from the Utah Jazz would come and speak to all 10,000 white Utah children about why you should try to improve your game instead of try hard in school because NBA players can make millions of dollars.

I had no business participating in Jr. Jazz. I was incapable of dribbling a basketball. I didn’t understand most of the basic rules. And, frankly, I hated playing.

But by the time I really realized that I hated playing basketball, my parents had already paid the fee and I had been issued an oversized jersey.

I treated Jr. Jazz more like a dodgeball league. I spent every minute of every practice just trying to avoid the ball as much as possible. I spent every second of every game attempting to look as busy as possible and trying desperately to make sure that I was sufficiently guarded by the other team so no one would get any crazy ideas about passing the ball to me.

Because I signed up for Jr. Jazz all on my own, I had been randomly assigned to a team of 12-year-old boys, all of whom were friends outside of the sport.

During the two years that I played with this team, I didn’t learn a single person’s name. And they didn’t learn mine. Because several dads would show up to each practice, I never was sure who, exactly, was our coach. And because I have a form of facial blindness, I often couldn’t recognize my own team when I showed up to games.

Jr. Jazz games were played on Saturdays at the local high school, which had a gym that was large enough that four games could be simultaneously played on four courts that were separated by a large curtain.

Because of my inability to recognize my own teammates, on two separate occasions, I started playing in the wrong game for a wrong team, only to be kicked out once people realized that no one knew me.

I eventually learned a trick for finding my team. After several months, I noticed that there was not one, but TWO sets of twins on my team. Two sets of very tall twins. And so, rather than just guess and possibly huddle with a group of kids I had never met in my life, I would wander the gym until I found a team with two sets of tall twins.

I was meant to be CIA operative. Not a basketball player.

I dreaded Saturday mornings more than I ever dreaded anything in my life. I would have given anything to retrieve Betty’s yarn ball instead of playing this game.

But when our season ended that first year, the coach announced that he had a sign-up sheet for anyone who wanted to play again the next year together. Noticing that my entire team had huddled around this sign-up sheet, I decided that if I didn’t also sign up, I would be a quitter. And I would let the team down.

And I didn’t want to devastate them like that.

And so, even though there was nothing in this world that I hated more than Jr. Jazz, I signed up for a second year.

The second year was identical to the first. I played dodgeball at weekly practice. I identified two sets of twins to find my team on Saturday mornings. I never once touched the basketball. And I never learned a single person’s name.

I was relieved when that second season finally came to a close, knowing that I would have at least a few months to rest before doing this whole song and dance a third time.

On our last day I turned to a child, whose name I did not know, and asked him where the sign-up sheet was. And to my utter delight, this child informed me that the team was splitting up. They decided not to play for a third year.

The reign of terror was over.

I literally skipped all the way home.

Home was one mile away.

It was the most athletic thing I had done in two years.

A few weeks later, I was contacted by one of the children of the neighborhood who had decided that it was time for our crew to join Jr. Jazz. He called me first because he knew I was already a veteran at the sport considering my years of experience. And he suggested that maybe Jr. Jazz basketball would be a better fit for us than the Jolly Green Giants had been a few years before.

Flattered that I was being recruited, and forgetting that I hated Jr. Jazz more than anyone has ever hated anything, I accepted the offer to basically be the team captain and I signed up with the children of the neighborhood to play Jr. Jazz basketball for a third year in a row.

Unfortunately, I was an average basketball player on my new team. And now instead of one child out of 12 playing dodgeball at practice, 12 children out of 12 played dodgeball at practice.

We fought during games about who had to sub in next.

Kids in the game would plead to be pulled out every time they ran past the coach on their way back and forth across the court.

The coach was Mikey Anderson’s father. He had agreed to coach us because no one else wanted to. He had never played a game of basketball in his life and he wasn’t really sure of the rules.

We lost every game. Usually the refs would say that we forfeited at halftime and just end the game, even though none of us had told the refs that we were forfeiting. But I don’t remember a single one of us protesting the refs’ decision in any game.

One time Tim Ipson scored a basket.

We rode that high for three weeks.

There was a rumor in our neighborhood after that that Tim Ipson might make the NBA one day.

Spoiler alert: he didn’t.

We were all relieved to find out that we only had one game left of this season. And we had all agreed that Jr. Jazz was going to be a one and done for our team. We wouldn’t sign up for another year.

Our spirits were high that Saturday when we arrived at court 2 in the Bingham High School gym for our final game.

We looked to the other side of the court to see which team would be beating us that day. We politely waved and nodded, for we were incapable of intimidation.

And that’s when I noticed it.

Two sets of very tall twins.

Our competitors—the team that would be beating us that day—was my old team.

The treachery.

The lies.

They had told me the team was splitting up. What they forgot to tell me was that the team was only splitting up from me.

I couldn’t believe they had done this.

And suddenly, the realization of what had happened started a fire in me I didn’t previously know was possible.

I felt a determination for The Sports that I had never before felt.

This was it. On that Saturday, I was going to play basketball.

I was going to dribble up and down alllll over that court.

I was going to make so many baskets that they would have to start using calculators to figure out my team’s score.

I was going to make this old team sorry for ever betraying me the way they had.

I strutted out to the center of the court and began stretching so they would know I meant business.

I occasionally gave menacing glares in their direction so they would know I wasn’t there to play; I was there to win.

The game started and four minutes later we were losing 20 to zero.

I knew I would need to change my plans a bit. I wasn’t going to be able to win this game by myself. And I was aware that were going to be deemed forfeiters at halftime. So I adjusted my goals. I wouldn’t try to win this game. But I would try to score one basket. Then the two-twinned team would see that I was the best player on my new team and they would see my potential and how I was just being held down by a bunch of no-good players—besides Tim Ipson Tim Ipson was exceptional because of that one time he scored a basket—and they would be sorry that they ditched me.

For the first time in three years I had to completely change strategies. Instead of running away from the ball like a game of dodgeball, I had to try to run toward it so that I could have a chance of scoring a basket.

I spent the next seven minutes doing just that. The score was now 40 to zero. And I was actually sweating from running so much. I wondered if this was why all of my teammates on the two-twinned team always seemed so wet after every game and practice.

And as I wondered this, the ball suddenly fell into my hands. I didn’t know if it had been passed to me or if it had bounced off of the backboard and come my way or if angels and intercepted it and reverently placed it in front of me so I could show the world what I was made of.

I was standing behind the three point line. I normally wouldn’t have attempted something so ambitious the first time I ever got possession of a basketball, but I was certain I couldn’t dribble it or hold onto it long enough to get to safer territory.

This was my chance. I would probably never have an opportunity to hold a basketball again.

And so, with a prayer on my lips, and with all of the strength I had in me, I launched that ball upward and forward.

Spectators later told me that it looked like I was having a seizure when I threw it.

But that didn’t matter. All that mattered was whether the ball would go through the hoop.

All that mattered was that I was about to prove everyone wrong.

The ball floated through air for an eternity. It floated through the air in slow motion. It floated through the air for so long that in my memory I can see the looks of horror on my teammates’ faces. I can vividly recall the shock of my parents’ in the stands. I can remember the surprise of the two-twinned team who had never seen me attempt to score a basket in my life.

The ball floated through the air, finally curving downward toward the basket, and then, without further ado, it went straight through the hoop.

I did it.

I scored a basket.

There was a new Tim Ipson in town.

I didn’t wait for the ball to hit the floor before I started celebrating.

I took a victory lap around the entire court, screaming and pumping my fists in the air like I had won the whole game.

I ran toward the children of the neighborhood, fully expecting them to raise me in triumph.

Sure, we hadn’t won the game, but what we did was going to be talked about like the Miracle on Ice. They would make a movie about it one day.

And then, Tim Ipson yelled to me. “You scored for the wrong team.”

I scored for the wrong team.

In all of the commotion, I had failed to notice that when the ball landed in my hands, we were on the other team’s side of the court.

The buzzer rang. And the refs announced that we had forfeited.

The score was 43 to zero.

After three years I finally scored a point for the two-twinned team. The only problem was that I was not longer of a member of that team when I did it.

We were directed to the center of the court to walk in a line and tell the opposing team “good game.”

When I got to the last person, one of the twins, he shook my hand and said “good job today. Is this your first year playing Jr. Jazz?”